If you’ve worked with PostgreSQL long enough, you’ve probably heard this sentence before:

“PostgreSQL is safe because everything is written to WAL.”

It sounds reasonable.

It feels reassuring.

And it’s only half true.

This misunderstanding — confusing WAL with actual data persistence — is one of the most common PostgreSQL misconceptions.

It doesn’t usually break your database.

But it does lead to bad tuning decisions, mysterious performance issues, and very slow crash recovery.

Let’s clear it up once and for all.

Table of Contents

The Misunderstanding That Refuses to Die

Most developers believe something like this:

See also: Mastering the Linux Command Line — Your Complete Free Training Guide

Transaction commits

→ Data is written to WAL

→ Data is safely on disk

→ Job done

So when they hear about checkpoints, the reaction is often:

“Why do we even need checkpoints? Isn’t WAL enough?”

This is where things quietly go wrong.

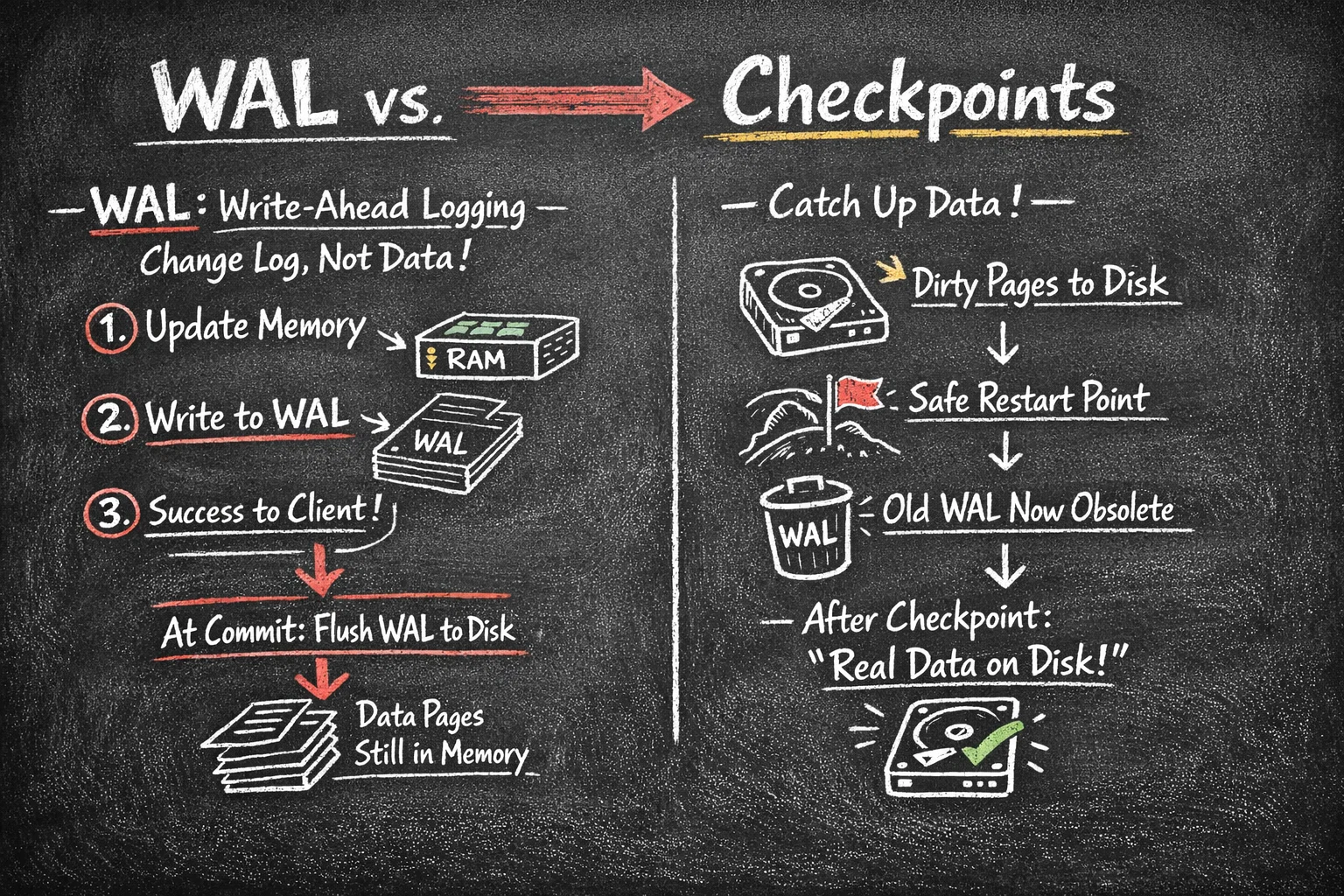

What WAL Actually Does (And What It Doesn’t)

WAL — Write-Ahead Logging — is not where your data lives.

WAL is a change log, not a database.

When PostgreSQL modifies a row, it does three different things, not one:

- It updates the page in memory (shared_buffers)

- It writes a description of the change to WAL

- It returns success to the client

At commit time:

- WAL is guaranteed to be flushed to disk

- Data pages are NOT required to be written yet

That’s the key detail most people miss.

WAL answers one question only:

“If we crash, can we re-apply committed changes?”

It does not guarantee that the data files are already up to date.

So Where Is Your Data Right After COMMIT?

Right after a commit, your data might exist in three different places:

- ✅ WAL (on disk)

- ✅ shared_buffers (memory)

- ❌ data files (maybe not yet)

That’s intentional.

Writing data files is expensive.

PostgreSQL delays it on purpose to batch I/O efficiently.

And this is exactly where checkpoints enter the picture.

What Checkpoints Actually Do

A checkpoint is the moment PostgreSQL says:

“Let’s make the data files catch up with reality.”

During a checkpoint:

- Dirty pages in memory are written to disk

- PostgreSQL records a safe restart position

- WAL before that point becomes irrelevant for recovery

After a checkpoint, PostgreSQL can honestly say:

“Everything before this point exists in real data files.”

Without checkpoints, PostgreSQL would still be correct —

but recovery would be a nightmare.

WAL Helps You Survive a Crash

Checkpoints Help You Recover Fast

Here’s the difference that matters in practice:

Without recent checkpoints

Crash happens

→ PostgreSQL must replay WAL from a very old position

→ Startup takes a long time

→ Business waits

With regular checkpoints

Crash happens

→ PostgreSQL starts from last checkpoint

→ Replays only recent WAL

→ Startup is fast

Both are correct.

Only one is operationally acceptable.

Why This Confusion Leads to Real Problems

This WAL vs checkpoint misunderstanding usually shows up as:

1. “We don’t need to tune checkpoints”

Then performance randomly drops every few minutes.

2. “Let’s reduce WAL size aggressively”

Suddenly checkpoints happen every 20 seconds.

3. “Recovery is slow, but hardware is fine”

The last checkpoint was 40 minutes ago.

None of these problems are obvious at first.

They all trace back to thinking WAL equals data persistence.

Why PostgreSQL Separates WAL and Checkpoints

This design is not accidental. It’s one of PostgreSQL’s strengths.

By separating:

- logging changes (WAL)

- from persisting data (checkpoints)

PostgreSQL gains:

- High write throughput

- Flexible tuning

- Predictable recovery behavior

But only if you understand both sides.

A Simple Rule of Thumb

If you’re running PostgreSQL in production:

- WAL tells you what changed

- Checkpoints decide when it becomes permanent

- Monitoring only one of them is incomplete

If you see WAL growth but never look at checkpoint behavior,

you’re flying blind.

How Checkpoints Work

The Checkpoint Process Flow

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Checkpoint Triggered │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 1: Identify all dirty pages in shared_buffers │

│ (Pages modified but not yet written to disk) │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 2: Write dirty pages to data files │

│ • Spread over checkpoint_completion_target period │

│ • Minimize I/O impact on normal operations │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 3: fsync() to ensure data is on physical disk │

│ (Not just in OS cache) │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 4: Write checkpoint record to WAL │

│ Records: LSN, timestamp, redo location │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 5: Update pg_control with checkpoint location │

│ (Used during crash recovery) │

└────────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Step 6: Mark old WAL files for recycling/removal │

│ WAL before checkpoint can be safely discarded │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Timeline Example

Time: 9:00 9:05 9:10 9:15 9:20

│ │ │ │ │

Data: ──────────────────────────────────────────────────►

│ │ │ │ │

WAL: ═══════════════════════════════════════════════►

│ │ │ │ │

CP: ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆

│ │ │ │

└─ CP1 └─ CP2 └─ CP3 └─ CP4

Legend:

◆ = Checkpoint

─ = Normal operations

═ = WAL accumulation

If crash occurs at 9:17:

- Recovery starts from CP3 (9:10)

- Replays WAL from 9:10 to 9:17 (7 minutes)

- Does NOT replay from 9:00 (17 minutes)

Types of Checkpoints

1. Timed Checkpoints (checkpoints_timed) ✅

Trigger: Controlled by checkpoint_timeout parameter

Characteristics:

- Predictable, scheduled occurrence

- Smooth, spread-out I/O

- Preferred for system health

Example:

-- checkpoint_timeout = 5min

09:00:00 → Timed checkpoint

09:05:00 → Timed checkpoint

09:10:00 → Timed checkpoint

2. Requested Checkpoints (checkpoints_req) ⚠️

Triggers:

- WAL size reaches

max_wal_size - Manual

CHECKPOINTcommand - Database shutdown (normal modes)

- Certain DDL operations (CREATE DATABASE, etc.)

Characteristics:

- Forced, reactive response

- Can cause I/O spikes

- High frequency indicates tuning needed

Example:

-- max_wal_size = 1GB

-- Heavy write workload generates 1GB WAL in 2 minutes

09:00:00 → Timed checkpoint

09:02:00 → Requested checkpoint (WAL hit 1GB) ⚠️

09:04:00 → Requested checkpoint (WAL hit 1GB again) ⚠️

09:05:00 → Timed checkpoint

3. Special Checkpoints

- End-of-recovery checkpoint: After crash recovery

- Shutdown checkpoint: Before clean shutdown

- Restartpoint (on standby): Similar to checkpoint on replicas

Checkpoint Configuration

Key Parameters

1. checkpoint_timeout

-- Default: 5min

-- Range: 30s to 1d

-- Recommended: 10min to 30min for most workloads

ALTER SYSTEM SET checkpoint_timeout = '15min';

Impact:

- Lower value: More frequent checkpoints, faster recovery, higher I/O overhead

- Higher value: Less I/O overhead, slower recovery, more WAL accumulation

2. max_wal_size

-- Default: 1GB

-- Recommended: 2GB to 16GB depending on write volume

ALTER SYSTEM SET max_wal_size = '4GB';

Impact:

- Lower value: Frequent forced checkpoints, I/O spikes

- Higher value: Smoother operation, longer recovery time, more disk usage

3. min_wal_size

-- Default: 80MB

-- Minimum WAL size to maintain between checkpoints

ALTER SYSTEM SET min_wal_size = '1GB';

Purpose: Pre-allocates WAL space to avoid overhead of creating new segments

4. checkpoint_completion_target

-- Default: 0.9 (90% of checkpoint_timeout)

-- Range: 0.0 to 1.0

ALTER SYSTEM SET checkpoint_completion_target = 0.9;

Impact: Spreads checkpoint I/O over this fraction of the interval

checkpoint_timeout = 10min

checkpoint_completion_target = 0.9

Checkpoint I/O spread over: 10min × 0.9 = 9 minutes

Reduces I/O spikes!

5. checkpoint_warning

-- Default: 30s

-- Logs warning if checkpoints happen closer than this

ALTER SYSTEM SET checkpoint_warning = '30s';

Log output when violated:

LOG: checkpoints are occurring too frequently (24 seconds apart)

HINT: Consider increasing the configuration parameter "max_wal_size"

6. log_checkpoints

-- Default: on (in PostgreSQL 15+)

-- Logs checkpoint statistics

ALTER SYSTEM SET log_checkpoints = on;

Example log:

LOG: checkpoint starting: time

LOG: checkpoint complete: wrote 16384 buffers (25.0%);

0 WAL file(s) added, 3 removed, 5 recycled;

write=25.789 s, sync=0.456 s, total=26.245 s;

sync files=142, longest=0.234 s, average=0.003 s;

distance=131072 kB, estimate=131072 kB

Final Thoughts

WAL is not the database.

Checkpoints are not optional housekeeping.

They are two halves of the same durability story.

Once you truly understand that difference, a lot of PostgreSQL behavior suddenly makes sense:

- performance dips

- recovery time

- I/O spikes

- tuning trade-offs