In the intricate world of computer networking, the Domain Name System (DNS) acts as the internet’s phonebook, translating human-readable domain names like “google.com” into machine-readable IP addresses.

For Linux users, understanding how to check and verify the currently used DNS server is a fundamental skill for network troubleshooting and management.

This article provides a complete guide on the various methods available in Linux, complete with command outputs to make finding your DNS server effortless.

Table of Contents

1. The Classic Approach: /etc/resolv.conf

Applicable to: Virtually all Linux distributions.

For many years, the primary file for configuring DNS in Linux has been /etc/resolv.conf. This plain text file lists the nameservers that the system’s resolver library should query.

To view the contents of this file, use the cat command:

cat /etc/resolv.conf

The output you see will vary.

On older systems or systems with manual network configuration, you might see a direct list of DNS servers:

Generated by NetworkManager

search mydomain.local

nameserver <b>8.8.8.8</b>

nameserver <b>8.8.4.4</b>

In this example, the DNS servers are clearly listed as 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4.

On modern distributions like recent versions of Ubuntu, Fedora, and Debian, this file often points to a local DNS caching service:

See also: Mastering the Linux Command Line — Your Complete Free Training Guide

This file is managed by man:systemd-resolved(8). Do not edit.

nameserver <b>127.0.0.53</b>

options edns0 trust-ad

If you see 127.0.0.53, it means your system is using a local systemd-resolved stub resolver. To find the actual upstream DNS servers, you should use the resolvectl command, detailed next.

2. The Modern Standard: resolvectl and systemd-resolved

Applicable to: Modern distributions using systemd, such as Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, Arch Linux, and their derivatives.

Most contemporary Linux distributions utilize systemd-resolved, a system service that handles network name resolution. The resolvectl command is the best tool for inspecting its settings.

To see the current DNS server information, run:

resolvectl status

The output will be detailed, but you should look for the “Global” or specific interface sections to find the server.

Global

Protocols: +LLMNR +mDNS -DNSOverTLS DNSSEC=no/unsupported

resolv.conf mode: stub

Current DNS Server: 192.168.1.1

DNS Servers: 192.168.1.1

8.8.8.8

Link 2 (enp3s0)

Current Scopes: DNS

Protocols: +DefaultRoute +LLMNR -mDNS -DNSOverTLS DNSSEC=no/unsupported

Current DNS Server: 192.168.1.1

DNS Servers: 192.168.1.1

In this output, Current DNS Server shows the server actively being used (192.168.1.1), while the DNS Servers list shows all configured servers. This is the most accurate method on modern systems.

3. The Power of dig (Domain Information Groper)

Applicable to: Often needs to be installed manually, except on specialized distributions like Kali Linux.

Tools like dig, nslookup, and host are excellent for testing and verifying that your real DNS servers are working correctly.

By default, they will talk to the local 127.0.0.53 cache, but their real power lies in letting you query any DNS server directly.

The dig (Domain Information Groper) command is a powerful tool for DNS diagnostics. If it’s not installed, you can add it:

- Debian/Ubuntu/Mint:

sudo apt-get install dnsutils - CentOS/Fedora/RHEL:

sudo dnf install bind-utils(oryum)

To find which server responds to your query, simply dig any domain:

dig google.com

Look at the bottom of the output for the SERVER line.

;; Query time: 12 msec

;; SERVER: <b>127.0.0.53#53(127.0.0.53)</b>

;; WHEN: Mon Aug 11 02:15:45 UTC 2025

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 55

The SERVER line clearly indicates that the query was answered by the DNS service at 127.0.0.53.

4. The Versatile nslookup Command

Applicable to: Widely available, but may require installation from the same packages as dig.

The nslookup command is another classic tool for querying DNS servers.

- Debian/Ubuntu/Mint:

sudo apt-get install dnsutils - CentOS/Fedora/RHEL:

sudo dnf install bind-utils(oryum)

Run it with a domain name to see the server that provides the answer.

nslookup google.com

The server information is displayed right at the top of the output.

Server: <b>127.0.0.53</b>

Address: <b>127.0.0.53#53</b>

Non-authoritative answer:

Name: [google.com](<http://google.com/>)

Address: 142.250.180.14

...

The Server and Address lines show that 127.0.0.53 was used for the lookup.

5. The Simple host Command

Applicable to: Generally included in the same dnsutils or bind-utils packages as dig and nslookup.

The host command is a simple utility for DNS lookups. For our purpose, using the verbose (-v) option is best to see which server was used.

host -v google.com

The final line of the output will tell you where the answer came from.

...

;; ANSWER SECTION:

google.com. 256 IN A 142.250.72.238

Received 44 bytes from <b>127.0.0.53#53</b> in 23 ms

The `Received ... from` line confirms the query was handled by `127.0.0.53`.

Conclusion

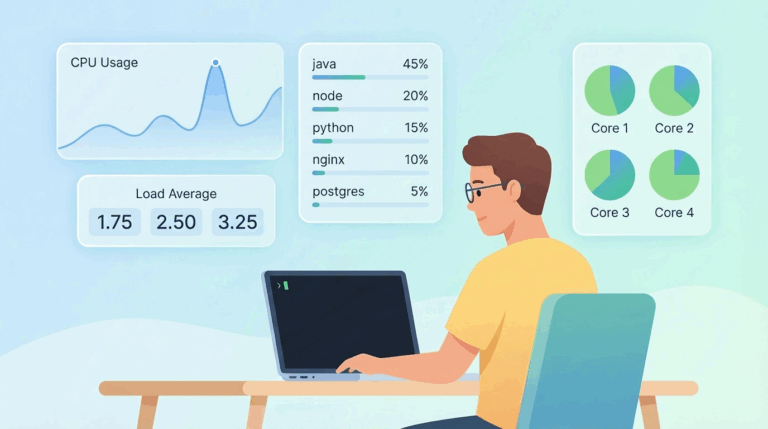

Knowing how to check your DNS server in Linux is a crucial skill.

For modern systems running distributions like Ubuntu and Fedora, resolvectl status provides the most definitive answer.

For a quick check or on older systems, cat /etc/resolv.conf is useful.

And for detailed troubleshooting, the dig, nslookup, and host commands not only perform the lookup but also clearly identify the DNS server that provided the response.